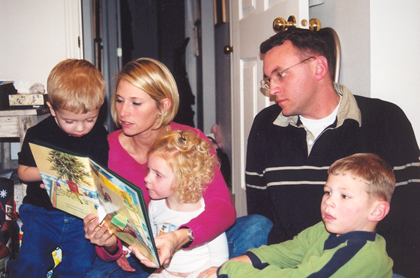

With Caitlin’s permission, I’m participating in a project this month by writing the abbreviated version of Caitlin’s cancer journey to share on social media. It has been amazing to write all these memories down and look through the pictures of this time in our lives. Since I’ve never written about the early days, I’m going to also share them here.

Caitlin was diagnosed with brain cancer when she was three years old, just days after Christmas. The details of the hours before and after diagnosis are seared into my memory, never to be forgotten. We had driven from my parent’s house were we had celebrated Christmas and Caleb's birthday, straight to the hospital. A drive that would normally take around three hours took much longer due to our need to stop frequently to care for Caitlin. She was having seizures every few minutes. As Clint drove he watched Caitlin from the rearview mirror and silently sobbed.

Our nurse was waiting for us as we walked in the doors of the clinic, she took one look at Caitlin and ran for the doctor. We were immediately sent to another hospital ER for a CAT scan, and then we waited and waited for the dreaded news. The ER staff would huddle together, speak in hushed voices, glance our way, and then disperse, only to do this again every little while. I remember thinking how annoying this was but in my heart I knew I didn't want to know what they were whispering.

After what seemed an eternity, a nurse came to get me (while Clint was outside speaking on the phone with my parents) to tell me our pediatrician was on the phone and needed to speak to me. Our kind, tenderhearted pediatrician had to break the news to me through his own sobs that our baby had a brain tumor.

We were released from the ER with a prescription for anti-seizure medication and orders to go to Primary Children's first thing in the morning. Caleb had been picked up by a neighbor and I was so anxious to go get him, to have him with us. After getting the children in bed, Clint and I spent the whole night getting ready for the unknown. We had no idea how long we'd be in the hospital and what to expect while we were there. The car was unpacked, clothes were washed and bags repacked. There was no sleep and lots and lots of tears. I kept finding myself in the kids room, kneeling over Caitlin in her bed, holding her while sobbing and praying. Before this moment in my life, I had no idea how much a heart could hurt.

Clint and I had no experience with the ins and outs of hospital stays, so we were unsure what to expect. It turns out; it was a lot of anxious waiting.

Caitlin was admitted and immediately hooked up to medications to help get the seizures under control and a MRI was scheduled. We were told the medication would make her tired and lethargic; however it had the complete opposite effect. Our normally sweet, easy going child turned into a hyper terror. To add to the problem, she had lost her ability to walk on her own. She wanted to move around and couldn't, and it was a challenge to keep her on the bed in the little room. We also had visitors coming and going and our room felt like it would burst at the seams. It was chaotic and suffocating.

Our only refuge was the Forever Young Playroom. Once we learned that we were on hospital timing and "the doctor will be here to see you soon" really meant, sometime in the next four or so hours, the doctor will stop in for two minutes to talk to you (or not), we kind of took things into our own hands. We would take Caitlin to the playroom where we could sit on the floor with her and let her move around. Usually we had the place to ourselves. We would stay until we were finally called back to the room over the hospital loud speaker.

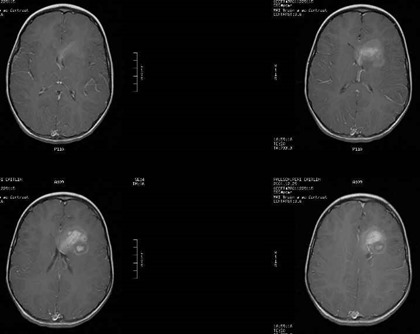

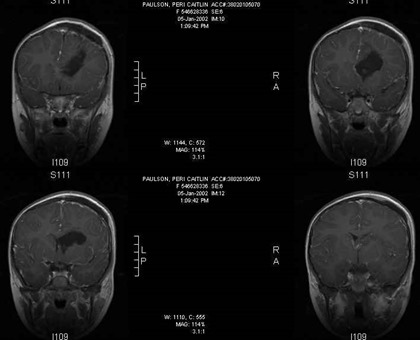

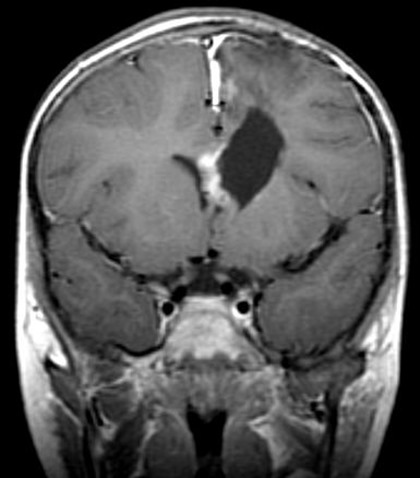

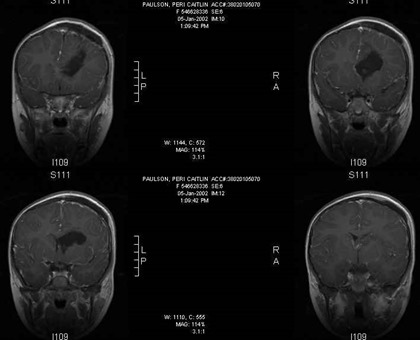

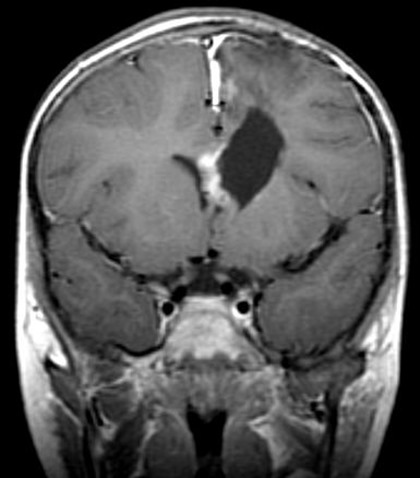

We learned from the MRI that Caitlin's tumor was located in the front left lobe of her brain and was the size of a golf ball. It would be necessary to have surgery to remove it and learn the pathology. After three days of hospitalization, we were released to go home on New Year's Eve to rest up for surgery that was scheduled on January 2, 2002.

After feeling like we’d been living in a glass box for days, we were ready for the privacy of our own home. Once we were on our way though, there was this feeling of vulnerability, loneliness, and like we didn’t belong in the real world anymore. Normal things like driving on the freeway and stopping at a store for milk felt wrong and foreign. It felt like everything had changed, but really I guess we were the ones who had changed.

Some of our friends came over that night with dinner and to let their kids play with Caitlin. It was good to have a distraction. We were blessed to have a close group of friends in our neighborhood; they supported, loved, and cheered us on from the very beginning.

Early on January 2, 2002, we headed back to Primary Children’s for surgery. I’ve never written about these early days, so I’m sure I’m forgetting a lot of information, but really, that’s probably a good thing. There was a lot of paperwork to be filled out and we signed our names and gave our consent to the most absurd things… permanent brain damage, disability, paralysis, death. I didn’t feel qualified to be a parent, a mother.

We met with Caitlin’s neurosurgeon. I don’t know what it was about him, but we trusted him immediately. The only thing I remember about that visit other than going over the risks of surgery again, was asking him if he had gotten a good night sleep. I needed to know he was prepared for hours of delicate surgery on my baby.

We kissed our tiny girl and then watched as her bed disappeared behind the swinging doors of the surgical room. My grandma, aunt, and friend, Jennifer came to wait with us, as my parents had taken Caleb home with them. We ended up in a waiting room with the parents of children having routine surgeries. They talked loudly, watched TV, and ate. The thing that was most annoying to me though was their laughter. How dare they laugh? Clint and I couldn’t even concentrate long enough to participate in conversation. There was a lot of blank staring and getting lost in thought.

We were told we’d receive periodic phone calls with updates, but our first update was given in person by a nurse. He came out to let us know the skull piece had been removed and the doctor was in the brain. Clint and I shared this indescribable look. We both knew what brain surgery meant, but I think until that very minute, it hadn’t sunken in. Our baby was having surgery, in her brain.

Caitlin's surgery lasted most of the day. When it was over, our neurosurgeon came into the waiting room to get us.

The surgery had gone well and Caitlin had been moved into the PICU. Now we needed to wake her up to see if she would recognize us and have the ability to speak and move her right side. She was so pale and had tubes and wires coming out of everywhere. I was surprised to see how little hair they’d shaved to do the surgery.

We woke Caitlin up and she immediately moved her right hand to her head and whispered, “Oooohhhhh, my head hurts.”

I don’t remember anything else about this day other than our doctor coming back to check on Caitlin and telling me the initial pathology report didn’t look good and that it would be days before the full report would be completed. The relief of having surgery over was immediately replaced with a deep fear and sadness.

The night of the surgery was crazy. The PICU was full of children, and for one night Clint and I were given one of the little sleeping rooms off the PICU waiting room. We didn’t feel good about leaving Caitlin though so we decided to take shifts. I stayed with Caitlin, and Clint went to get some sleep.

The PICU consists of many curtained off areas in one big room. Some had their curtains completely closed, some had the sides closed with the front curtain open to the main room, and others were fully exposed. We had our curtains open to the front and I was able to look around and hear some of the conversations. I wondered how all these children had ended up here just days after Christmas, and then I wondered how many had been here for Christmas. This was all so foreign. I remember there was one nurse I watched all night and I couldn’t believe how inattentive and uncaring she was. Our nurse was wonderful and I was grateful for that. Caitlin was her only patient that night.

In the early morning hours Clint came to check on us and as things had been going okay, we both decided to go back to our little room and sleep.

In the PICU the parents of the patients are asked to leave for an hour or so in the morning and in the evening while the doctors do their rounds. When we were allowed back in to see Caitlin I was surprised at how much worse she looked. Her little eyes were swollen and when they were open you could see her pain in them. She slept most of the day and we just sat next to her bed touching her hands and cheeks.

Later in the day our neurosurgeon came to the PICU to find us and told us pathology had come back faster than expected. He asked us to come with him so we could have a private discussion, and then led us through the back hallways and staircases to his conference room. I was so anxious and scared; I think I prayed the whole way there.

It’s funny how your brain works in times of great stress. It’s as if you are allowed only a certain amount of information before your mind turns off. There are some things I remember about this day so vividly, and there are also giant gaps.

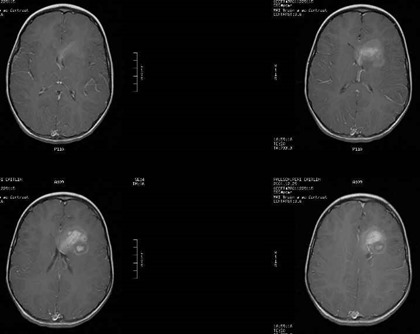

Caitlin had a post-surgery MRI that morning and our doctor showed us the before and after scans. It was a little unnerving to see the hole in Caitlin’s brain where the tumor had been. The rest of the information was presented as good news/bad news. We learned the pathology of the tumor had come back as a Grade 1-2 Oligodendroglioma. Apparently that was supposed to be “good.” I can’t remember the word cancer being used, and felt like the overall message our neurosurgeon was giving us was positive.

The bad news was the MRI showed the tumor had not been fully removed and the consensus of the medical team was that a full resection would give Caitlin the best chance of survival and it would be less likely she would need additional follow-up treatment. Our neurosurgeon then gently repeated the message in words we could understand; Caitlin would need another brain surgery the following day.

I was beginning to feel braver about asking questions and I remember asking our doctor what it was like to perform brain surgery. He thought about it for a minute then gave the analogy of having a cup of yogurt (like Yoplait) with the middle filled with cottage cheese. It was his job to remove all the cottage cheese without disrupting the surrounding yogurt. I admit every time I eat yogurt, I think of that.

While we were talking, our doctor was playing with a puzzle of a model brain. He had taken it completely apart and was putting the pieces back together as he spoke. The last piece was giving him trouble and his attempts to force the piece caused the whole puzzle to break apart. He started over, and then put it down on the conference table unfinished and said something to the effect that he always had a hard time putting it back together the right way. Clint and I shared this look and just started laughing. It was the absolute wrong thing to say to parents of a child you had just operated on and were planning to operate on again. Somehow though it struck us as funny.

We went back to the PICU and I called my mom to tell her the latest news. She told me I didn’t sound like myself and I remember telling her I was just tired. Clint and I were both so exhausted. It was time for the parents to leave so the doctors could do their rounds. When we came back the night shift was coming on and lucky us, the inattentive nurse from the night before was assigned to Caitlin. There would be no sleep for us that night; there was no way we would leave our baby alone in her care.

The day of the second surgery began with another MRI. This time Caitlin’s brain was mapped to pinpoint the exact location of the residual tumor. I couldn’t believe we were doing this again; she was still so sick and weak.

The time of the surgery came quickly and we told the PICU nurse that Caitlin couldn’t go into surgery without a blessing. Clint and I were alone and we didn’t have much time, so a call was made over the hospital loudspeaker for a Latter-Day Saint (LDS) priesthood holder. Within minutes we were told someone was on the way. Clint and I were both in fragile states and with the impending risks of another surgery, we asked this kind hospital employee if he would offer the blessing. We had never met this man and we’ve never seen him since. While I can’t remember what was said, I will always remember how we felt. The words spoken were beautiful and powerful and personal. I knew the Lord was aware of this child.

Once again Caitlin was wheeled off to surgery and Clint and I headed for the waiting room to settle in for a long wait. There was another couple in the room and they seemed to share our level of concern and anxiety. Eventually the woman spoke to me and said she’d noticed us in the PICU. We learned they were there with their baby daughter who was having heart surgery. We continued to talk and share details and when some of my friends showed up later to wait with us, they joined in the conversation. This would be the only connection we would make with another family while in the hospital. We’ve maintained a friendship with this couple over the years, but it wasn’t until their oldest son was diagnosed with cancer four years later that we knew our meeting was inspired.

Caitlin had survived two brain surgeries in three days. Back in the PICU her body started reacting to all it had been through resulting in high fevers and the need for blood transfusions. After a few days, she was finally moved out of the PICU into a private room.

Each day Caitlin became more alert and interested in the things happening around her. Gifts and visitors came in steady streams, and her daily schedule included therapy of every kind, even a visit from a therapy dog. She had a real bath, the first since the morning of her initial surgery, and started to eat small amounts of real food. It finally felt like we were coming to an end of a nightmare.

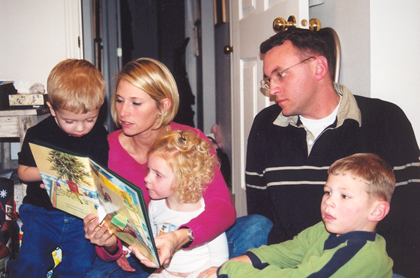

We were finally released from Primary Children’s and went home to Caleb. We spent the winter healing, Caitlin physically, and the rest of us emotionally. After all the craziness of the diagnosis and surgeries it wasn’t until we got home that the weight of what we’d just been through hit us full force.

Spring came and Caitlin was getting her light back, not just her health, it was more than that, it was like a curtain had been lifted from her eyes. We took her in for her first follow-up MRI and our neurosurgeon told us something was showing up on the scan, but said it was most likely scar tissue. Around this time, Clint and I chaperoned a fieldtrip to the zoo with Caleb’s class and we took Caitlin with us. She looked so healthy and happy. I remember taking pictures of her that day, her curly hair was filling in and covering her scar, and she was just so happy to be at the zoo with all the big kids. It really hit me that she had come so far in just a few short months.

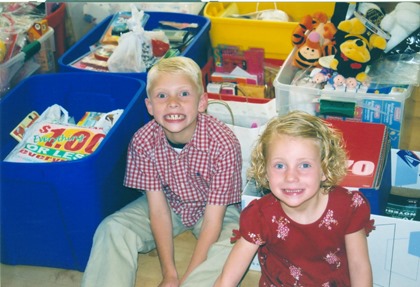

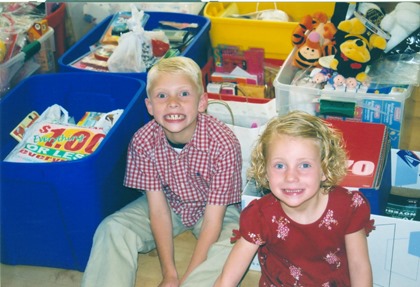

In the fall, Caitlin started preschool and turned four years old. We celebrated by hosting a service project for Primary Children’s, gathering toys, games, books, and art supplies from family and friends. It would be the first of three times we’d celebrate her birthday this way.

We met again with our neurosurgeon in November after having another follow-up MRI. Our neurosurgeon asked how everything had been going and if we’d noticed any changes. Clint said he didn’t think there had been any, but I started listing off some concerns I’d been having. Our doctor listened to everything I had to say and wrote a few notes in Caitlin’s file. We were completely blindsided when he told us the MRI confirmed new growth. The tumor was back and this time surgery wouldn’t be a viable option.

I don’t possess the vocabulary or the writing skills to adequately describe how it felt to be told Caitlin’s tumor had returned. All I know is it hit me harder than the initial diagnosis had. We decided to go to my parent’s house for the weekend for the love and support we so desperately needed to come to terms with this news.

Early the following week we had an appointment at PCMC in the hematology-oncology clinic. At the time this area of the hospital was located in a quiet area, just off the back entrance and down a small hallway. The department consisted of a waiting room with a TV, a table to make art projects, and a toy area. The receptionist area was behind glass and you talked through a little window. Once the patients name was called, weight, height, blood pressure and temperature were taken, and then you’d be taken around the corner to a long hallway of rooms. Each room consisted of a bed, rocking chair, a rolling stool, a sink, and plenty of medical equipment.

The first time we came to this clinic, I looked around and it made my heart hurt. The children around us looked so sick with their bald heads and the circles under their eyes. I felt so sad that they had this horrible disease. I’d gone my whole life without really knowing anyone who had had cancer and it didn’t seem right at all that children had it. I’m not sure what was going on with me, shock, denial, whatever, but I didn’t realize my very own child had cancer. No one up to that point had used “that” word.

The first person we met with was a sweet Fellow. She was motherly and kind; however our conversation became rather awkward when she realized we hadn’t been told we were dealing with more than just a benign brain tumor. I remember she looked concerned, left the room, and then came back and clearly communicated that Caitlin had cancer.

We then met the doctor who had been assigned our case, and our social worker. It was explained to us that the tumor had grown back in the same location, but it was located deeper in the brain than before and surgery would be too great a risk. Our medical team had discussed radiation, but felt Caitlin was too young and the risks to her brain outweighed the benefit of attempting to kill the tumor with this type of treatment. We were left with chemotherapy as our best option.